Gristled surfers, ink-garlanded muscles and snap-thin-bone bodies guard the beach in Maroubra, all intent on getting their share. The waves boom and crash in this Aboriginal place of thunder, then hiss and crinkle as they meet land, easing to welcome sand-soft toes and a toddler’s giggles.

Strung out between Coogee to the north and Malabar to the south, Maroubra curls beneath the brow of of Long Bay, home to the notorious Correctional Centre and the Anzac Rifle Range. Beneath this insidious gaze Maroubra shines as an example of beach life with white sands in a cursive swoop, legendary surf breaks, open space, chock-full milk bars and a proud working class narrative.

Here the dog days of summer never fade, wolfishly roaring deep into the night. Thongs and shorts, skimpy bikinis, nanna one-pieces, striped towels, floppy hats and flesh are the uniform of the day. Sandy hands clutch hot chips and rainbow-flavoured drinks, beads of chill dripping into the sand while gulls whirl and collide above, savagely bent on their target.

Families flock to the beach with guttural joy,

“I’ve told ya’s before ya little buggers! Youse gotta wear’em. Yeah darlin’, that lady’s got boobies… Nah mate, nah. Leave it on yer head… JAYDEN! WILL YOU BLOODY LISTEN! COME BACK HERE NOW… Ah, sodjus”

spilling across the sands. Mums corral slippery kids into bathers and out of picnic baskets, an old couple take the air, long-limbed teens flop lazily in front of each other and a tradie stands solemnly, watching the surf. There’s a retro family feel, people piling out of battered station wagons to escape hot seats, nippers racing into the waves, corned beef sarnies wrapped in white paper and past-their-prime gumball machines:

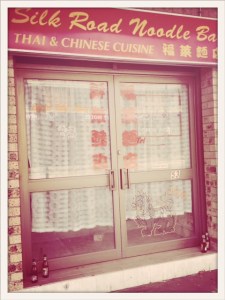

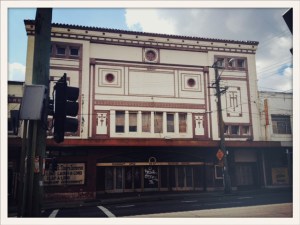

Back from the sweep of sand the Maroubra Seals sports club stands over the front with an imposing gesture, a mechanic, a hotel and a Thai joint it’s only companions on a strip that should be bustling with business:

There is a palpable sense of space. To the south of the beach Magic Point is an unexpected swathe of bushy camouflage, the towers of Long Bay looming in the distance; to the north, apartment blocks line the front in an orderly if dated line. It sparks a rare thought: where is everything? Expansive beach? Check. Surf club, sports club, RSL club? Check. A sprinkling of diners and caffs? Check. Pub? Check. Thai? Check.

That’s it. That’s all there seems to be. Where are the shops? Where are the cars? Where is the sterile anonymity of the local supermarket with its Argentinian garlic and Brazilian mangos? Too-small-for-you and made of nylon clothes? Red Rooster?

Nope. Not here.

Tiny McKeon Street leads away from the ocean and is dotted with a hamburger joint, a posh neo-European-Australian fusion place, an organic caff and a milk bar. The secretary opts for fish, chips and hot tea [I can always rely on her when tempted to guzzle cold beer and smoke Cubans] and settling down beneath a shady gum we watch as life strolls blithely past. The secretary comments that she finds Maroubra vaguely sparse, that there is an emptiness she cannot put her finger on. I remind her all her fingers are attached to hot chips and she agrees, maybe it’s nothing.

She is right though. There is a shrouded sense of something else, and the scent of a counter culture lingers. Though it is lacking the coastal ostentation of its more northerly sisters, Maroubra is not without pretence. It’s no secret that for all the recent gentrification (of which I find little evidence beyond boarded up work sites, wet concrete and the noise of hidden machines), the suburb is tattooed. It belongs.

Raw with pride, the Bra Boys are Maroubra’s infamously territorial surf mob, known for their clashes with authority, fierce loyalty to each other and an autobiographical doco entitled Bra Boys: Blood is Thicker Than Water that lifted the lid on the darker side of the suburb.

The surfing brotherhood with the flesh-inscribed motto My Brother’s Keeper, worn as an inky lei, is a fierce reminder of the poverty and social dislocation in the area, of the rite of passage from boy to man and then on to the testosterone-fueled angst that lolls on car bonnets, struts the front and owns the sand.

Koby Abberton

Image courtesy of Newsphoto

As a term, surf culture tastes vanilla and invokes frangipani-patterened boardies and Hawaiian Tropic, bleach blonde hair and the smell of salt and sex wax. In Maroubra a darkness lurks behind the stereotype, shadowed with controversy, hard stares and the sense of solidarity ingrained within an estranged extended family.

Image courtesy of Newsphoto

At the My Brother’s Keeper concept store you can buy surfwear emblazoned with slogans and gaze at walls tiled with faded photographs that tell the story of the tribe. There is a message that reads:

My Brothers Keeper is not a Gang, it’s not a Fashion Label it is a Way of Life. It is a belief that nothing comes before your Friends & Family. It is for all Races. Whether you are Australian, Asian, American, African, Middle Eastern, European or from Fucking Mars…

Amidst the clamour of distaste for the Bra Boys, the veiled taints of racism and a pervading fear, it is clear that this is a family and it protects its own. Though the angst sweats uncomfortably in some of the creases of Maroubra, the tribe are part of what gives this place its unconventional, retro beauty.

The early years

Born to surf

[Images courtesy of Newsphoto]

In a forest of houso blocks just metres from the front, the sun shines gently through mature trees, sofas stand sentinel in front yards strewn with life, and kids hang off the gates. There is a vibrancy, of life lived despite its hardships.

Steeped in rank seawater and rust, Maroubra has been described as a ghetto. While it is a hard-edged city surf beach that has a visceral realism, a rare find in a plastic fantastic world and the natural beauty is undeniable, this is a long way from the ghetto.

The pounding waves define not only the bay but the life its people lead. The ocean slamming into the rocks is the inveterate battle of the elements, the shaping-up of the forces of nature. It conjures a sense of perpetual change, of expectation and escape and there is no denying the serpentine break born of this conflict is at the wild heart of this gritty suburb.