Depending on where you are from, Kelpies are fiercely intelligent working dogs who live to herd stock, or mythical Gaelic river spirits that take the form of damp horses that lure the unfortunate to a watery death. Either way, they are mesmerising and programmed to lead you astray.

According to the Macquarie Dictionary: /əˈstreɪ/ (uh’stray)

adverb 1. out of the right way or away from the right; straying; wandering.

–phrase 2. go astray,

a. to fall into error

b. to have a moral lapse.

c. to be lost or mislaid

All of which are apt when you drunkenly decide it’s imperative to attend the annual Kelpie Muster, and only realise it is 12 hours and 39 minutes and 1,160.1 km from Sydney along goat tracks that meander through Victoria to the South Australia border, suspiciously close to Mt Gambier… once you hit the road.

Fortunately, I am not alone. The houndsman has deigned to ride pillion, if only to keep the hounds in line. While he is devoid of deerstalking hat, walking cane and/ or hunting livery, he is cheery, at least until I advise him of the open wastes that lie ahead.

The Australian Kelpie Muster is the highlight of Glenelg Shire’s June long weekend, drawing a circling murmuration of thousands of these beautiful creatures and their country-worn owners to Casterton, settled in 1834, but home to the Konongwootong Gundidj clan of the Gunditjmara People for thousands of years before this.

It is billed as a sun-drenched autumn festival, crowds lining the streets, bagpiped marches, RSL-led parades, and dogs everywhere you look. Except the closer we get, the more extreme the weather, an Antartic tantrum of ice-fringed squalls that rock the van and unnerve the Kelpies.

On slick roads, we eventually slide into Casterton, days after we left. Expecting fanfare and excited barking, it is silent and dark, encouraging nervous date-checking and a scramble into the only open pub to suss out the scene.

Which, unsurprisingly, is like every other remote country town pub, watchful eyes, oilskins steaming around the fire, “yeah, nah, fuck off mate!” a staccato beat when conversation starts up, and the smell of beer and chip fat.

Parked up out the back of the pub, rain sideways, and half cut, I fall asleep in a tangle of canine limbs, hoping I haven’t made a horrible mistake.

Dawn is punctuated by council carnies yelling obscenities and trailing plastic bunting, and the yipping of a thousand-plus dogs, an orchestra conducted by the musicians themselves. Outside, we have 100 new neighbours, and Kelpies more excited than a dog with two tails to meet their people…

Akubras jut at every angle atop grizzled features scored into deep contours of life lived hard and well. Small kids barrel in the direction of the fairy floss, the Carlton is tapped, and the main street is gussied up in her best frock, a hint of high vis at her extremities.

The Kelpies are abundant, every colour, coat and creed (cattle/ sheep/ chicken/ goat/ stick/ ball) prancing in front of proud owners, bowing deeply to other dogs, a prayer stance known only to them.

The parade is six-deep, to see the tribe of dogs 700 strong proudly snaking through the town, followed by old timers, stockmen, the fireys and kids from the school.

These beauties yelled out “G’day, nice pups!” as they rolled the EJ Holden passed…

And the pup on horseback squeaked as she rode by, her excitement streaked down her master’s thigh…

There’s the sprint and the high jump, the hill climb and more, a phalanx of fur four-stepping in glee, the calls of the owners a comedy soundscape of “gits” and “go Monkey go!”

It’s a showcase of talent and grit in which the Hill Climb is the pinnacle. Pups are called from the top of Blueberry Hill, which towers 50+ metres above us, slick and commanding. Shrill commands disperse into whispers by the time they reach the dogs’ ears, yet somehow they understand, climbing valiantly towards a dot on the summit…

The Stockman’s Challenge features sodden sheep and downcast horses, but the Kelpies are on point, eager to prove their worth.

This is a breed that can run 60 km in a day, with a hawk-like devotion to a job they find fun, sleeping inside the stone rim of the fire pit at night, to cradle the warmth. They are as happy herding a feather or leaf if no stock are available, and can find their way home when lost and alone. To the people here, the farmers and stockmen, ringers, breeders, trainers, and owners, they are our ride-or-die.

The muster is like a high-school reunion for dogs. Black and tans, blues, silvers, reds, blondes, there’s a hierarchy, a pack order, and within that, there are striations of when and how. Our urban Kelpies are free-er somehow, less expected to do anything but be with us, a novelty thanks to their colour and city road skills, less working, more w-o-r-k-i-n’…

At night, the rank and file are kennelled in the showgrounds, a snarl of outlying settlements beyond the pub. Behind a wall of mud-streaked tow rigs, hot coals smoke in homemade braziers in neat, utilitarian camps hung with collars and muttering with sound. We are welcomed in all, tails wagging in delight, bourbon shared in tin mugs, the stories of the mobs tangling in laughter lifted high in the night air.

The defining emotion at the muster is one of love, a canine-human equation that has an infinite result, loyalty and respect squared. The only fight is a fracas at the pub, speed-dealer sunnies at dusk, and an overturned table. Over ‘his missus’, apparently. The Kelpies are better behaved entirely…

Sunday breaks with a steady stream of patois statistics over the tannoy: “Dolly is from Molong, an 18-month-old uncut bitch, who leans to the left on a mob of stock, but will take direction”, I think is what he said. Not quite what I was expecting, but the Kelpies have their ears pricked, so it looks like we’re heading to the trials that are a precursor to the working-dog auction.

His call continues. a minaret to the believers, graziers lined up along the fenceline, watching, intent. One by one, the dogs are led out into the paddock to show off their skill, low to the ground, stalking, nipping, herding the stock into the corner and through the crush, their desire to work evident in each bright-eyed acknowledgement of barely uttered commands. They are judged on their intelligence, instinct, stamina and obedience – and ‘a tendency to nose-bite’.

It is tempered by the hopeful promise in mournful eyes of each dog tethered on heavy chains in the shed, awaiting their turn – or the outcome of the auctioneer’s gavel.

I would take them all home, these bright-eyed pups, but their lives are lived in service, their incredible instinct dedicating them to a role they are born to. Added to which, I am not in the bidding for prices that can exceed $45,000.

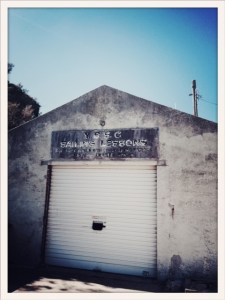

Legend has it, Warrock Homestead is the birthplace of the Kelpie, although this is heavily debated. We go, anyway, and find nothing of the bright intelligence of the dogs. Instead, a crumbling pile – on show for a price – drags threadbare memories through the mud. We are handed a scrap of paper with badly kerned words, and told the cream teas are over. The map dictates where to go to see this ‘outstanding nineteenth century Western District pastoral complex, featuring 36 hand-built Gothic and Colonial style buildings’. It is riven with sadness, and icy to the touch, ghostly shivers sneaking up your spine in every emptied room.

“Here the mistress took to a single bed until the end of her life, her unborn babe buried beneath the breezeway”

“Here, ‘the Blacks’ were made to sleep on broken slats slumped on mud floors”

“Kennelled here, the estate’s Irish wolfhounds were released regularly to hunt native dingos”

There’s a negligence here, lost care and hollowed lives. Station log books show the tight curl of disrepair, this hard land complicit in every aspect of life. Family photos are patina’d with sadness, eyes downcast, a visual memory of pain. George and Mary had one stillborn child. He took up with the maid. Mary died of heartbreak.

It is a pleasure to leave Warrock, with its dark history and claims of ‘the first Kelpie stock’. Because if you scratch the skin of this story, the truth exposes a lie. The landowner of Warrock refused to give any pups from his Scottish collie stock away, determined to keep the collie line. One was secreted out to a drover, however, and traded for a horse. The drover – Gleeson – named her Kelpie for the malignant water sprite of Celtic lore. She was mated to ‘a black prick-eared male’ named Moss in Ardlethan in NSW, and it is this litter that is believed to have forged the bloodlines of the breed, named Kelpie’s pups, or ‘Kelpies’ for short.

We take to the open roads, heading home to put the urban Kelpies into training for next year, starting with laundromats and how to use them…

They’ve got 11 hours and 48 minutes to master the skill.